Part 4 Cecil St. - The East End

No. 20 Cecil Street

The building currently occupied by the Fung Leun Tong society was, during the late 1950s, 60s and 70s, known as the Donavalon Centre. Originally a private home, it was bought in 1956 by Donald Moore and two other members of the Negro Citizenship Association, and converted into a ground-breaking recreation centre for the West Indian community of Toronto. In addition to housing the United Negro Improvement Association and the Toronto Negro Citizenship Association, the Donavalon Centre offered a wide range of activities and services for members and supporters, including dances, teas, Sunday programs, and insurance coverage. It published a quarterly newsletter.

Donald Willard Moore (1891-1994) was born in Barbados, emigrated to Canada about 1912, and worked as a sleeping car porter, then dyer, launderer and dry cleaner on Spadina. He became a community leader and civil rights activist, fighting to change Canada's exclusionary immigration laws. In 1954 he led a delegation to Ottawa, with 34 representatives from the Negro Citizenship Association, as well as from unions, labour councils, and community organizations. They presented a brief which included the following statement:

“The Immigration Act since 1923 seems to have been purposely written and revised to deny equal immigration status to those areas of the Commonwealth where coloured peoples constitute a large part of the population. This is done by creating a rigid definition of British Subject: 'British subjects by birth or by naturalization in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand or the Union of South Africa and citizens of Ireland.' This definition excludes from the category of 'British subject' those who are in all other senses British subjects, but who come from such areas as the British West Indies, Bermuda, British Guiana, Ceylon, India, Pakistan, Africa, etc... Our delegation claims this definition of British subject is discriminatory and dangerous.”

This landmark brief led to a relaxation of immigration laws, opening the door for West Indian nurses and domestic workers to get jobs in Canada. By 1955, Moore's work with the governments of Jamaica, Barbados, and Canada enabled domestics to gain permanent residency after one year of work.

A sizeable black population lived in and around the Kensington-Spadina-Alexandra Park area in the 20thcentury, having arrived successively via the Underground Railroad, migration from Nova Scotia, and immigration from the West Indies and the UK after the war. In addition to live-in domestic servants and caregivers, their main employment was in the railway, hospital and service industries. Cecil Street provided meeting and relaxation space:

This was the 1955 Provincial election. Joe Salsberg had a lot of support in the black community. He had been active in the fight for an Ontario Human Rights Code, following a municipal decision to disallow Jews and blacks from using certain Toronto swimming pools.

For the younger black crowd, the nearby Paramount Tavern, at 337 Spadina & Baldwin, became a popular hangout from the 1960s onwards. Its décor was shabby, its plumbing primitive, and it had a reputation for mixing drugs, hard drinking and prostitution. But its blues and reggae music was funky, the dancing wild, and the whole scene often electric.

The Zionist Institute and the Workmen’s Circle School, at Cecil & Beverley

No. 16 Cecil, the next house east of No. 20, was built in the mid-1880s as an office and surgery for Dr. Edward William Spragge. It was an integral part of his splendid 3-storey residence whose main entry was around the corner at 206 Beverley.

A prominent member of the city elite, he co-founded the Ontario United Empire Loyalists with neighbour C.E. Ryerson. A Canadian Practitioner 1920 obituary depicts him as a sports all-rounder: “an excellent cricketer, a fine oarsman, a skilled sailor and an expert tennis player”. In 1913, he sold his 16 Cecil/206 Beverley mansion to the Zionist Institute and moved to Yorkville.

The building became the home of the Workmen‟s Circle or Arbeiter Ring. This North American organization initially embraced a wide spectrum of leftist ideologies, ranging from Bundism, Territorialism and Marxism, to Anarchism. The common cause was a commitment to progressive, secular, working-class Yiddishkait. To this end it created the Nationaler Radicaler Shul, later named the I.L. Peretz Shul, after the famed Yiddish poet. It held most of its classes at nearby 194 Beverley (now demolished and part of Beverley Public School). Religion was not on its curriculum (the Shul was strictly secular); nor was Hebrew. The language of instruction was Yiddish, the mameloshn (mother tongue) of the vast majority of Toronto‟s Jews. History was taught from the working-class, immigrant perspective of recent Eastern European arrivals rather than that of the more affluent and longer-established Jewish population from Western Europe, which congregated around the Holy Blossom Temple (on Bond St from 1897 and Bathurst & Eglinton from 1938), Goel Tzedec (on Richmond from 1883; at University Avenue and Elm, then Dundas, from 1903; at Bathurst & Eglinton from 1955), and Hebrew Men of England (from 1922 at Spadina & Baldwin, then from 1960 at Bathurst & Sheppard).

Adele Reinhartz attended the Peretz Shul after its postwar move north. Her parents were socialist holocaust survivors from Poland, affiliated with the Jewish Labour Bund: “The Bund valued Yiddish over Hebrew, the Diaspora over Israel, and culture over religion. At the Peretz Shul, we did not study Mishnah or Talmud, or the prayer book. Instead, we learned Yiddish, read the works of the great Yiddish authors, and sang songs from the Yiddish theater. We also studied Jewish history, from the Babylonian exile in 586 BCE through the Maccabean revolt; the revolts against Rome; the Golden Age in Spain; the Inquisition and expulsion; the pogroms, blood libels, and ghettoes of Europe and Russia; the creation of the State of Israel, and Jewish life in North America. In our corner of the Jewish community, Jews did not attend synagogue, even on the High Holidays, nor did we fast on Yom Kippur or refrain from bread on Passover. We had our own rituals and traditions, our secular seders commemorating the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, our Sunday evening gatherings to eat, sing, and argue about politics. We had a strong Jewish identity rooted not primarily in the Holocaust but in the rich secular Yiddish culture in which our parents had been raised.

This poster, taken from the souvenir book for the 1922 convention, shows Toronto’s two Workmen’s Circle schools – one at 131 Maria Street in the Junction (top & middle right); the other at 194 Beverley (middle left).

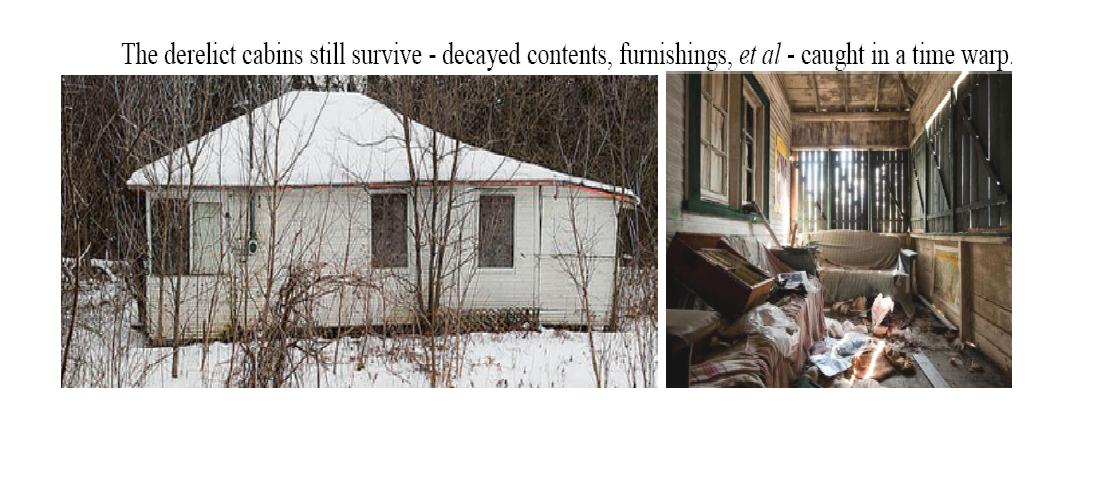

As part of its mission, the Arbeiter Ring ran Camp Yungvelt (Young World) in Pickering, with cabins for weekend and summer family stays. Thousands of young Jewish children spent time there from 1926 until it closed in 1971.

The 1917 Bolshevik Revolution back in Russia, and the formation of the Communist Party of Canada in 1922, provoked a serious crisis within the Workmen‟s Circle. Pro-Soviet militants came into conflict with social democratic members, and a fierce struggle broke out over its future direction. An ideological and organizational showdown at its 1922 National Convention, held in Toronto, resulted in expulsion of the communists. In response, in 1926 they formed the Jewish Labour League, which based itself at the Alhambra Hall on the SE corner of Spadina & College, and threw itself into organizing progressive, national Canadian unions in the garment industry.

The Labour League established its own rival leftist summer camp in Brampton (Camp Naivelt or „New World‟). After the war, concerts were held there by the likes of Paul Robeson, Pete Seeger and Phil Ochs. The Travellers folk group began life there. This camp still flourishes today.

In 1945 the Labour League merged its regional branches into the United Jewish People‟s Order, which, from 1960, based itself at the Winchevsky Centre, north of Bathurst & Lawrence, home to a famed Toronto Jewish Folk Choir and the Winchevsky School. Meanwhile, the Zionist Institute at 16 Cecil/ 206 Beverley housed not only the Arbeiter Ring, but a disparate and ever-changing kaleidoscope of Jewish organizations – socialistic, labour/secular, athletic, even orthodox religious – which shared a broad commitment to establishing a Jewish homeland in Palestine, which Britain‟s 1917 Balfour Declaration had pledged to facilitate. Purged of its Marxist-Leninist activists, the Institute became a haven for both lofty intellectual discourse and lower-octane community recreation.

The Institute facilitated the formation of Free Loan associations, and in many other ways brought together the working class and more bourgeois elements of Toronto‟s Jewish community. It played an important role in the 1930s and 1940s when the spectre and reality of the Nazi holocaust stalked Europe and held all elements of the diaspora in its thrall.

In the 1950s, the Workmen‟s Circle uprooted itself from 206 Beverley and moved to 471 Lawrence West, just east of Bathurst, along with the Peretz School. It is still there today, albeit much diminished. The Zionist Institute (renamed the Zionist Centre) moved to 651 Spadina, and thence to 188 Marlee Avenue, near Lawrence & Bathurst.

In 1956, 206 Beverley/ 16 Cecil was bought by the Polish Combatants Association (SPK), a war veterans group, which shared space with several other Polish organizations. In 1972 they deemed the rambling old Victorian house too restrictive, and demolished it. By 1973 a modern building had been erected. It went on to serve as a meeting-, concert-, dance- and banquet- hall for the Legion and for the broader Polish community.

The hall is well-appointed, classy and colourful inside, but its exterior resembles a Soviet-era bunker. Its rear end and sunken car-park, flanking Cecil St, might well be classified as an eyesore:

But there‟s no accounting for taste.

Concrete Toronto: A Guide to Concrete Architecture from the 50s to the 70s [2007] – a publication for cement enthusiasts – considers it an architectural gem: “The Polish Combatants Association Branch No. 20 offers expressive institutional Brutalism on a quite residential scale. Floating on piers over a sunken, open-air parking lot, the compact bulk of the building houses offices, restaurant and banquet hall, and remains a lively staple for the Polish community. A cast-in-place frame, and rugged precast „corduroy‟ concrete panels, have made the building a neighbourhood landmark within its Victorian surroundings….”

The Murray House and the Edelweiss Club

Right across from the Polish Club, on the opposite side of Beverley (at No. 207, on its NE corner with Cecil), there stands today an upscale complex of townhouse condominiums, completed in 2012.

This modern housing block elbows itself out a bit rudely into Beverley, past its elegant Victorian neighbours. Its design is a bland, unimaginative riposte to the „brutal statement‟ made by the Polish Hall over the road. The newborn 207 Beverley sits on the former site of a once vibrant, celebrated local institution

Nos. 205 & 207 Beverley had been the site of two separate Victorian homes from the 1880s well into the 1930s, occupied by a succession of professional households. From the 1940s to the 1970s, a one-storey kosher banquet and meeting hall called Murray House stood on the double lot. With its four dining rooms, it was a popular venue for the downtown Jewish community‟s gala events, association dinners, family celebrations (weddings, birthdays, bar mitzvahs, etc.) and cultural performances and social gatherings of all kinds. Its main nearby competitor was the more upscale Chudleigh House, 136 Beverley, now the Italian consulate.

In the late 1960s, as its clientele dwindled, the building was sold to the Austrian Club Edelweiss, a social and cultural organization of Austrian immigrants to Canada, established 20 years earlier as an offshoot of the post-war Canadian Society for Austrian Relief. As with the Polish Hall, it‟s unclear why this area of Toronto was chosen, as most German and central European settlement was further west, around High Park and South Etobicoke. But there had been a big influx of Hungarian refugees into the Spadina area after the 1956 Soviet intervention. Their homeland territory and culture overlapped with that of Austria, whose eastern region (Burgenland), close to the Hungarian border, was the main social base for Club Edelweiss. It functioned as a banquet hall for this community. The old Murray House interior was revamped to resemble an Austrian Bierkeller, and its licensed restaurant and bar were opened to the general public for lunch and schnitzel dinners. Steelworker classes walked over there for lunch from 25 Cecil. The Alpine interlude was relatively short-lived, however, and it was forced to close its doors in the late 1980s.

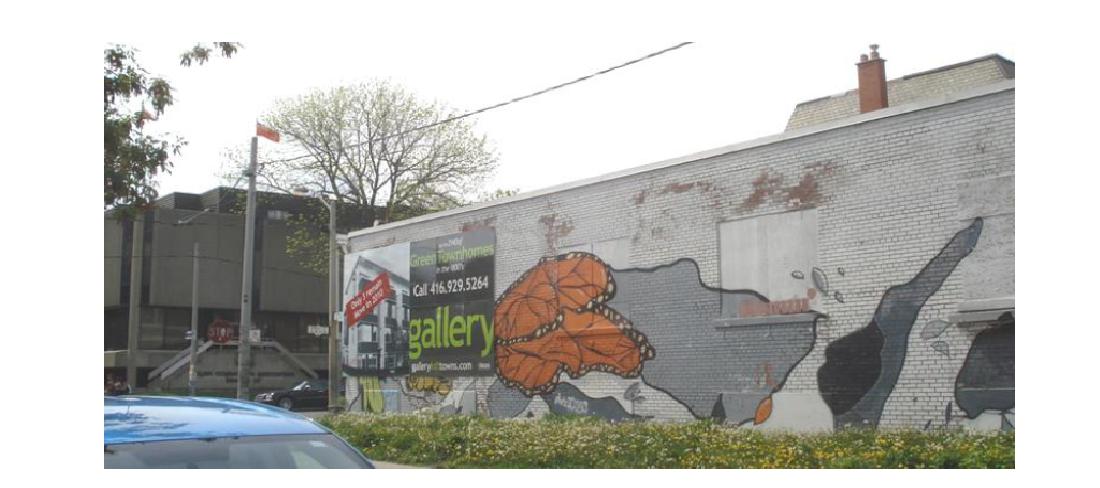

Eventually No. 207 Beverley re-opened as a nightclub, The Study Hall or Student Hall, run by a retired Toronto cop, aimed mainly at the young university crowd. It encountered licensing problems, amid complaints from neighbours about noise, fights, drugs and uncontrolled „raves‟. A fire in the late 1990s finally put it out of business, and the premises stood derelict for another decade, a boarded-up, flyer-pasted, graffiti-covered shell. By 2009, as the gentrification-driven property market scaled dizzy heights, its owner decided to cash in, to demolish, and to convert to condo townhouses. The units, listed for sale at close to $1 million each, sold out quickly.

The Hydro Block

They don‟t shout it out, but the modern housing units at Nos. 5-11 Cecil, at the eastern extremity of the Street, south side, deserve an asterisk beside their doorways. They result from a remarkable episode in Toronto‟s recent social history, and constitute a small corner of a site which has been justly flagged by the City for significant architectural and cultural heritage.

First, the social history: In the late 1960s, early 1970s, the provincial power utility, Ontario Hydro, quietly set about buying houses in the block bounded by Beverly, Baldwin, Henry and Cecil Streets. Its ultimate goal was to drop a huge 12-storey transformer station into the midst of this established residential community, in order to service downtown Toronto‟s growing electrical needs. It conducted a process of stealthy block-busting, so that most of the real estate had been swallowed up before the community realized what was happening. By the summer of 1970 many houses were already vacant and boarded-up, and consciousness finally dawned. Several East European immigrant owners willingly sold their property and moved to the suburbs, but so-called „hippie‟ and Chinese residents objected to the scheme and refused to be forced out. A multicultural neighbourhood group was formed to stop the redevelopment. July 1970 saw a protest demonstration on Baldwin, with several arrests, as a group of Americans tried to squat in two of the empty houses. This campaign tied in with a wave of community-based struggles across the City to save older residential areas from redevelopment, a movement that was steadily gaining momentum and political clout.

Meanwhile, a broad-based anti-developer group was already conducting a high-profile direct-action battle to stop construction of the Spadina Expressway. Initially promoted by the Ontario government, that project would have destroyed a thousand existing homes between Sheppard and Bloor, physically split several communities in two, and funneled commuter traffic into the heart of the downtown core. It would have radically transformed the whole Spadina area. Eventually, after four years of mounting opposition, the provincial Tories, under Bill Davis, relented. In the summer of 1971 they announced that the Allen Expressway (as it had been named) would not be allowed to go further south than Eglinton Avenue.

The energy from this major victory spilled over into the anti-Hydro Block struggle. In September 1971, Minister Allan Grossman – the local MPP (he who had defeated Joe Salsberg in 1955) and now the cabinet minister responsible for Housing - met with area residents to explain his Government‟s plan for the transformer station; he got a very hostile earful. Soon Queen‟s Park was forced to backtrack again. The December 1972 municipal elections gave control of City Hall to a group of anti-development reformers. Toronto‟s Planning Council designated Baldwin Street Village as a neighbourhood and commercial centre whose distinctive architecture and use should be protected for future generations. The original Ontario Hydro project was evidently doomed.

Then the second, proactive phase of the Hydro Block campaign kicked in: if not a giant transformer station, then what? Community activists argued for low- or mixed-income housing, and buildings that would reflect a positive, community-minded, street-level vision. And they demanded government resources, involvement and active intervention to make all this possible. This creative part of the struggle lasted another five years, until the new Hydro Block finally saw completion in 1978.

At first the Ontario Housing Corporation was put in charge of the development, but it was quickly assailed for its reluctance to seriously commit to „social housing‟. Heading into 1975, the Hydro Block community campaigners turned up the heat, helped by the active reform block on City Council.

Eventually Queen‟s Park bent in the face of relentless pressure. Responsibility for and control of the Hydro Block site was handed over to City Home, Toronto‟s newly-formed non-profit Housing Corporation. Celebrated architects Jack Diamond and Barton Myers were hired to design a residential project that would respect the scale and material qualities of the existing neighbourhood. Twelve fine original Victorian homes on Beverley Street, Nos. 181-203, plus a couple on Cecil, were preserved, and converted into multi-unit residences. On the other hand, the whole row of smaller, run-down cottages along Henry Street was deemed not salvageable and was demolished. In their place, an imaginative brick-built complex of housing units was constructed, stretching the length of the street between Cecil and Baldwin, broken up by stoops, large windows and glass walls, walkways and sunken gardens, all cleverly integrated with the existing housing stock at each end.

The Hydro Block complex now covers 6-28 Henry, 40-42 Baldwin, 181-203 Beverley and 5-11 Cecil, with a swathe of leafy park gardens hidden within its perimeter. It comprises the one long 4-storey townhouse/ apartment building and three 2-storey town-home complexes, as well as the historic houses. The development offers bachelor, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5-bedroom units. City Home has designated it as mixed income, with some units at market rent, and others geared to income. Local residents were originally given priority. Instead of the people-free behemoth planned by the electrical utility, the Hydro Block (as it continues to call itself, rather than the Beverley Place nomenclature preferred by city planners) became a model for „new urbanism‟, for balanced community development, for preservation and architectural integration of fine existing Victorian homes with new, low-rise in-fill housing. “Today, more than 20 years after it was built, the complex .. still stands as an elegant essay on dense urban living – the need for low-scale, individualized housing with front door access to the sidewalk.”

Old houses preserved on Beverley Street are an integral part of the Hydro Block.

As for the cultural, historical and architectural value of the site, this is best summarized in the City‟s own words, in officially designating the complex as of exceptional heritage significance:

The four-storey apartment building at 6 Henry Street has design or physical value as an important example of Modern architecture in Toronto that was planned to complement through its height, materials and massing the adjoining low-scale residential buildings. In the design, “the high-rise form was turned on its side and laid along the street,” showing “how high density housing could be achieved with architecture on a human scale”.

The interior organization is expressed on the exterior. The lower floors contain two-storey units with individual entrances on Henry Street and Cecil Street and private yards to the rear. The smaller apartments on the upper two levels are accessed from a glazed corridor on the third storey that overlooks the streets below.

Beverley Place has historical value for its direct association with an event of significance to the urban development of Toronto. In the early 1970s, a series of late 19th century house form buildings along Baldwin, Henry and Cecil streets were demolished for a proposed Toronto Hydro transformer station. Local residents and heritage activists joined forces to protest the plans in one of the first successful combinations of citizen activism and heritage preservation in Toronto. As a result, Beverley Place was constructed, blending new construction and saving heritage buildings in an established residential neighbourhood. Beverley Place has contextual value as it maintains and supports the late 19th century character of the Grange neighbourhood as it developed around the present-day Art Gallery of Ontario. Along the west edge of Beverley Place, the six semi-detached houses at 187-197 Beverley Street are included on the City‟s heritage inventory.

The heritage attributes of Beverley Place relating to its design or physical value as a representative example of Modern styling applied to an apartment building are found on the exterior walls and the flat roof, with particular attention to the elevations facing Henry Street (east) and Cecil Street (north). Rising four stories, the structure is clad with red brick with concrete coping. The principal (east) façade consists of a long street wall along Henry Street that is broken by recessed areas where paired entrances and flat-headed window openings are placed in the first floor, and balconies are introduced on the corners. The solidity of the wall is countered by the large window openings in the second floor, the glazing that illuminates the interior corridor on the third level, and the balcony doors in the upper storey. The fourth floor is set back, with angled brick walls dividing the units. The features described above continue on the north elevation on Cecil Street.

![No. 189 [entranceway on left] was for many decades the residence of world champion rower Ned Hanlan and his family.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/513f806fe4b03d61808647ba/1479846940924-CPU8OAJWQ17N3JN4HHMH/image-asset.jpeg)