Part 3 - Steelworkers on Cecil St.

From the late 1940s onwards, the United Steelworkers Toronto Area Council operated out of rented space: offices at 111 Richmond St. West, and a meeting hall over stores at 340 College St, west of Spadina (where the not-for-profit Kensington Eye Clinic now stands).

By 1953, led by Area Supervisor Don Montgomery, the Steelworkers were seeking a permanent building for meetings and staff offices. Their choice eventually came down to two sites. One, on Bay Street, was the vacant Wellesley Public School, later the site of the Sutton Place Hotel. The other was the Jewish Old Folks Home on Cecil Street: two Victorian houses – Nos. 29/31 & 33/35 - with a large two-storey addition at the back of No. 33/35. The Cecil site was finally chosen, at a cost of $90,000, because it offered more land and possibility for further growth. The Old Folks Home provided a $55,000 mortgage to facilitate the deal, which was completed in February 1954.

The Home‟s main facility at No. 33/35 Cecil, with its modern extension at the back, suited the Union's initial needs best. Its ground floor had had small private rooms for patients, which were converted into offices for servicing reps. A large nursing staff area was used for the secretarial pool. There was already a large meeting hall in the basement. And ample male and female washrooms.

The house next door, No. 29/31 Cecil, became known as the „Annex‟. It had been the Old Folks Home‟s first location, and was rather dilapidated. Two large rooms on its main floor had served as wards for elderly patients, as had much of the second floor; the building was well worn. A third floor was used only for storage. In the fall of 1954, when members of Locals 3589 & 3684 were on strike at the American Standard plant (then known as Standard Sanitary and Dominion Radiator), many volunteered time to clean up and renovate the Annex. The main floor was turned into meeting rooms, and an apartment was created upstairs for a caretaker – initially Charles Rox and his wife - whose job was part-time and unpaid, in return for free accommodation.

In early 1955, USWA support & servicing staff began to work out of 33/35 Cecil (including its rear extension), using the first floor offices and basement meeting hall. The Ontario Federation of Labour, the Doll & Toy Workers Union and a Brotherhood of Carpenters local rented the second floor. It remained OFL headquarters until it moved to Gervais Drive, Don Mills in 1968.

The next step was to create the Toronto Steelworkers Building Association (TSBA) as a non-profit foundation registered with the Ontario Government. Workplace Locals were asked to contribute to a Building Fund on a per-capita basis of 25 cents per member per month, and over 95 % agreed to do so. A committee also raised funds by holding Saturday night dances.

In early 1956 the remodelling of 33/35 Cecil began. The original front portion of the building [photo above] was considered beyond repair and torn down, but the larger, more modern extension at the back was preserved, and a new, small two-storey addition attached to its front, creating an entrance lobby. Offices and meeting rooms were added in the renovated basement and second floor; and a new furnace room and heating system was installed. The reconfigured building – now set well back from the street - became today‟s No. 33 Cecil St.

Buoyed by a post-war manufacturing boom in downtown Toronto and its suburbs, Steelworkers wanted to establish a solid, enlarged footprint on Cecil Street. A TSBA financial statement at the end of 1961 already referred to “prepaid architect‟s fees re proposed new building - $250”, and a Director‟s meeting in March 1962 contemplated buying properties to the east of #29-31 Cecil. The AGM in May 1962 heard its Executive Secretary speak of plans for “the erection of a new building to be situated on the site now occupied by the building presently known as the Annex. Brother Montgomery gave details of area, and presented .. architects proposals of lay-out.” The May 1964 AGM approved “the Building Programme as outlined by the Executive Secretary and General Manager”, at an estimated cost of $200,000. The February 1965 Directors‟ minutes even declared that “the new building.. is to be erected this spring.” Meanwhile acquisitions continued. In 1963 the TSBA bought #25 Cecil from the Minsker Farband Temple for $17,500, and #27 from the Folks Farein for $19,000. They tore down #27 in 1963, then #25 two years later. A plan was afoot.

In 1965 the TSBA also bought the original 3-storey Folks Farein headquarters, #23 Cecil, by then owned by a Jewish businessmen's club. The relatively high cost – $46,500 – reflected its good state of repair. This added a meeting room and washrooms on its first floor to the TSBA portfolio, and its second floor became a new apartment for the caretaker‟s family. This in turn enabled the TSBA, in 1967, to tear down the „Annex‟, a.k.a. „the old gray house‟, at #29-31.

<1930>, doorway of No. 23. Part of No 25 can be glimpsed on Right

By now the TSBA owned all the property from the laneway in the east – providing access to the backs of houses and parking spaces behind Beverley, Baldwin, Huron and Cecil – as far as #33 to the west. There was even some TSBA talk in 1965 of buying houses further west, i.e. from #37 towards Huron, “to square up the parking lot at the rear”.

The Steelworkers planned to clear the land they had been assembling over the previous 15 years, and to erect a custom-built union hall on it. The last step taken, in 1971, was to demolish the house at No. 23, leaving No. 33 as the only Steelworker building still standing on the street, with its ground floor serving as the union‟s interim headquarters. The rest had been flattened.

Architects Tampold and Wells had been hired as far back as 1961 to design a new Steelworker centre on the site. But in the mid 1960s, a wrench was thrown into the works by two alternative proposals, each of which sidetracked the original plan. Along with later delays in approval and construction, this postponed the building of the hall for another decade. The first scheme (a) was to build a new complex of union headquarters in the neighbourhood, under the aegis of the Ontario Federation of Labour. When that fell apart, and the OFL moved to Don Mills instead, a second idea (b) popped up: for a non-profit “Union – Community – Senior Citizens housing development”, to be aided by federal grants and municipal tax rebates.

(a) The Ontfed Complex

The Ontario Federation of Labour was the provincial body to which almost all unions were affiliated once the Canadian Congress of Labour merged with the Trades & Labour Congress in 1956. It had been renting cramped office space at 33 Cecil since 1955. In 1965 it set up its own Building Association, Ontfed, to search for land on which to erect its own Toronto HQ.

It approached the Steelworkers, its largest affiliate. Basically it proposed swallowing up the entire TSBA project into its own hastily-devised scheme: to mark Canada‟s 1967 Centennial by creating a central headquarters for the whole Ontario labour movement. TSBA Directors Meeting minutes outline the discussions. On 22 November 1965, Don Montgomery reported that “he had met as instructed with representatives of the Labour Council and representatives of the Ontario Federation of Labour, and both indicated that they were prepared to join with the Steelworkers and other party named to construct a new Toronto Labour Centre, and establish a new holding company to hold title to same and management of the said centre.”

The OFL hoped to erect its own $2m office building on Cecil, which would provide a hall, meeting rooms and offices for Steel‟s Toronto Area Council, and space for other unions. The TSBA, however, was determined that Steel retain its separate identity within any such venture rather than surrendering control to the OFL. A key meeting took place on March 10 1966 between Larry Sefton, Steelworkers Ontario Director, and Doug Hamilton & David Archer, leading officers of the OFL. The TSBA minutes are instructive.

First, Hamilton explained that, to finance its venture, Ontfed hoped to get 10 large unions to invest $100,000 each in common stock. Another $1½ million would be raised by selling preferred stock yielding 6%. They proposed to take over the Steelworker site, in return for shares in Ontfed. If not, they had another location in mind at Gerrard & Parliament.

Sefton replied that it was unlikely such an ambitious project could be completed by 1967, and that in any case Steel wanted its own building. He floated a longer term plan to jointly purchase and develop “all the property on the square bound by Baldwin and Cecil, Beverley and Huron Streets”. This could evolve into a dedicated Labour neighbourhood, with other unions encouraged either to join the Ontfed complex or to erect their own buildings alongside.

Hamilton explained that Ontfed urgently wanted to erect a 6-7 storey office tower in the area, to include meeting halls, but admitted that, to date, all it had acquired was an option to buy a couple of lots on Baldwin. Furthermore, “the main office building presently located at 33-35 Cecil Street did not fit in with his overall building program and was of no material use to him, but he said that the location was good and additional land could be assembled at prices the Ontfed Building Association could afford, and therefore he wanted to make some agreement with the Steelworkers to purchase all or part of their present holdings.”

Sefton reiterated that “with 96 plants organized in 77 local unions, the Steelworkers must retain their own identity”, and the meeting broke up without any agreement. An impasse had clearly been reached, although some half-hearted back-and-forths took place over the next few weeks. On March 15, Ontfed tabled an offer to buy the whole 23-31 Cecil frontage, 130ft x 188 ft deep, for $147,000 (i.e. $6 per sq ft), $100,000 of which would be paid for in Ontfed common shares. The TSBA could keep its refurbished property at #33. On March 28, the TSBA countered with a demand for $217,000 (i.e. $8.86 per sq ft), $100,000 in Ontfed common shares, $60,000 in preferred shares, and $57,000 in cash. A final Ontfed offer of $171,000 (i.e. $7 per sq ft) was firmly rejected at a 17 May 1966 TSBA Directors meeting, and the OFL henceforth transferred its gaze to a high-rise on Gervais Drive, in suburban Don Mills. Although the final abortive negotiations were ostensibly about price, the real issue was control, identity, and an ambitious quick fix versus a more carefully nurtured neighbourhood development.

In the meantime, Steelworker plans for a new building had been effectively put on hold.

(b) The Community Housing Development

Then, in late 1967, another TSBA scheme bubbled up. At a 27 November Directors‟ meeting, E.A. Bastedo of Reuben Corporation touted the benefits of a non-profit „Union- Community-Senior Citizens housing development‟, in which he offered to partner. He proposed a high rise building with 330 bachelor and one-bedroom apartments for seniors, plus offices and hall. The senior citizen element could attract provincial grants and low city taxes for 50 years, plus a favourable 50-year mortgage from the National Housing Administration. Meanwhile, to get extra frontage, Bastedo urged the TSBA to take an option on #37 Cecil to the west, “now owned by the National Hebrew Association” (i.e. Folks Farein). But six months later, the downside had sunk in: low rents would also be fixed for 50 years, after which ownership reverted to the city. Undeterred, the would-be developers proposed ditching the seniors‟ component, and instead suggested a „limited dividend‟ project, with occupants to include a mix of workers‟ families and students, perhaps a daycare too. Things were going round in circles ..

By mid-1968, the TSBA was back at square one, with limited finances. Its own earlier, more modest scheme, for a Union hall and offices on the site of 23-33 Cecil, was urgently revisited. Over the years, at least since the architect‟s drawings of 1961, the Steelworker building plan had envisaged two floors of offices, atop a sunken auditorium, meeting rooms, classrooms, a boardroom and lounge, a kitchen suitable for catering, a bar, washrooms, etc. Late in the day, as things began to gather momentum, a third storey was added.

The whole construction project then got the go-ahead. Hands-on management of the project was entrusted to Steelworker Staff Representative and Building Manager, John Fitzpatrick. He was initially under the tutelage of Area Supervisor Don Montgomery, Executive Secretary of the TSBA since 1954, but from the 1970s onward it became Fitzpatrick‟s personal baby.

But first, financing had to be arranged and city approval obtained. In 1969, the Steelworkers opened negotiations with the group of garment industry unions which were in the process of selling the Labour Lyceum on Spadina to a consortium of Chinese businessmen. These unions, headed by the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers, offered $200,000 for the 33 Cecil building and for the right to 14 spots in its back car park. But for reasons which today seem unclear, the City of Toronto kyboshed this plan by refusing to allow #33 to be split off from the properties the TSBA had accumulated, and by further stating that no permit would be issued unless the proposed new building was integrally attached to #33. To overcome the latter technical problem, the architect proposed creating an underground tunnel between 33 Cecil and the new hall (No. 25). This was indeed built, with steps down behind the hall‟s bar leading to a subterranean passageway across to #33. It‟s still there today, but as a blind tunnel, a fictitious link, since no real opening was made at the other end, only a tiny crawl-space beside a basement boiler room, through which it even a racoon might have trouble squeezing.

Faced with the city‟s denial of a separate deed for #33 Cecil, the TSBA and Labour Lyceum decided to become partners in the whole site. By their terms of agreement, the TSBA owned 75% of the property and the Lyceum 25%. The TSBA had full use and control of #25 and the Lyceum had use and control of #33, along with those parking spots. This sidestepped most of the complicated identity and control issues that had bedevilled the OFL negotiations.

What was the Labour Lyceum?

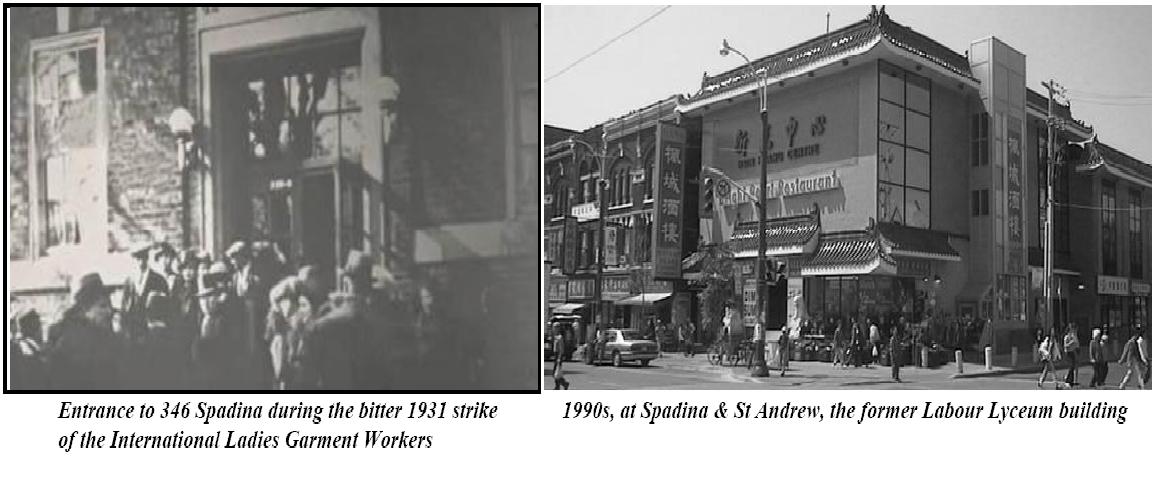

In its earlier years, from 1925, this storeyed institution occupied a large building at 346 Spadina & St Andrew. For almost half a century it had housed the offices of non-Communist garment trade unions, and had served as a hub for countless union activities.

But the Lyceum had been much more than a union office complex. Cooperatively funded by the sale of $5 shares to individual members, it had functioned as a bustling social centre for countless fraternal labour bodies and secular Jewish societies during the 1920s, ‟30s and ‟40s. It hosted lectures, rallies, dances, plays, poetry readings, concerts. Its events ranged from the purely social~

Famed labour activist and anarchist Emma Goldman spoke there several times (see flyer above), and lived nearby after her American citizenship was revoked. When she died in Toronto in May 1940, her body lay „in state‟ at the Lyceum for three days. The provincial CCF (forerunner of the NDP) held conventions there in the 1940s. In its heyday, the 1930s, the social-democratic Lyceum‟s intense rivalry with the communist-led unions – notably the Industrial Union of Needle Trade Workers - was an ingrained feature of working life in the Spadina area. But then came that post-war demographic ebb-tide. Spadina morphed from Jewish heartland into commercial hub of Chinatown. In 1971 the Lyceum building was sold to a Chinese consortium, which converted it into the Bright Pearl Seafood Restaurant (now the Hsin Kuang Centre). The roof was drastically remodeled, pagoda style, its brickwork resurfaced, and its entrance moved around the corner to St Andrew Street to accord with fen shui principles (with stone lions to deter reputed ghosts left from its early incarnation as a funeral home). The Lyceum, by then co-owned by the International Ladies Garment Workers, Amalgamated Clothing & Textile Workers, and Fur Workers unions, moved its headquarters to 33 Cecil. The influence of the textile unions had already waned, as Canadian manufacturing was steadily sucked offshore. „TORONTO LABOR LYCEUM‟ lettering is still visible on No. 33‟s façade, but its rationale and life had faded by the time it relocated there in 1972.

The 144 Huron footnote

When No. 23 Cecil was torn down in 1971, the union had to find new living quarters for the caretaker‟s family (by now Albert DePinto, a Steelworker from American Standard). For this purpose, the TSBA bought a small semi-detached clapboard house on the NW corner of Cecil & Huron – numbered 144 Huron, although its only entrance was on Cecil – at a cost of $23,000. It required extensive renovations, including digging out a basement by hand to create more space.

But there was a last-minute wrinkle. The purchase & use agreement between the Lyceum and the TSBA required Steel‟s Staff Reps to move from 33 Cecil, although its basement could still be used for membership meetings, and clerical staff could temporarily use an office built in its lobby. Steel originally planned to house its Staff Reps in short-term rented premises at the bottom of Spadina, but instead they opted to speed up renovation of 144 Huron to enable them to work there. So the caretaker moved into a rented flat on Baldwin until the new Hall was ready to accommodate all the support & servicing staff. Only then did the caretaker move into 144 Huron, which was tied to the job for all future occupants, notably Syl McNeil and Gerry Pope. The house was finally sold in 1998.

In early 1971, the City issued the long-awaited permit for the new hall, and construction began.

Unfortunately, once the frame was up, the City building inspector decided that the structural steel – supplied by Dominion Bridge, a USWA-organized company in Toronto, who also built the CN Tower - was not heavy enough, and needed reinforcement and bracing. He shut the project down. The architect disputed the need for this, but to no avail. Then the contractor and architect fought over who should pay tens of thousands of dollars for additional material, and for site security over the winter. The TSBA argued that the contractor and architect should split the burden, but, to avoid more delay, eventually it had to swallow much of the extra expense itself.

After a 12-month hiatus, construction resumed in earnest once weather permitted. After one last hold-up (due to inadvertent awarding of the heating system contract to a non-union firm, and subsequent re-tendering) the Hall was finally completed by the end of 1972.

On 1st November 1972, 14 Steelworker servicing staff and 6 secretaries moved into its first-floor offices. The union had been busily expanding and reorganizing meanwhile. Mergers had taken place within the labour movement, and the United Steelworkers had been joined by the Mine Mill & Smelter Workers and by District 50, United Mine Workers of America. These two unions had had their own Toronto headquarters, but now all came together under the roof of 25 Cecil.

Over the next few months the second floor was rented to the Communication Workers of Canada and some smaller unions. The third floor stood empty throughout 1973, but in the spring of 1974 the Lifeline Foundation moved in - a ground-breaking social service initiated by USWA Staffer Lloyd Fell, supported by employer companies, and chartered by Ontario‟s government. It helped, advised and referred workers struggling with addiction and with other personal & family issues.

Since then, the Hall‟s tenants down the years have included several other unions, including Local 4400 of the Canadian Union of Public Employees; the Union of Needletrades, Industrial & Textile Employees (UNITE); the Letter Carriers Union of Canada; and locals of the Communications Workers of Canada (later CEP). It has also housed such progressive social organizations as the Labour Council Cooperative Housing Foundation, the Ontario Council of Senior Citizens, the Unemployed Workers Council, Mayworks, Christian Peacemaker Teams, War Resisters Canada and i-Taxiworkers. The Lifeline Foundation still thrives there, along with other Steelworker Area Council initiatives like the Job Action Centre, the Injured Workers Program, the Toronto-Barrie Strike Assistance Fund, and previously the Steelworkers Credit Union. A Steelworkers Dental Clinic offers low cost dental care to the general public, at the rear of the basement of No. 33 next door. Cecil Street was the cradle of the groundbreaking Humanity Fund in the early 1980s under Staff Rep Gerry Barr – an international aid and solidarity organization, financed by voluntary member contributions – before it was adopted by the national union. The Women of Steel program, which develops the leadership potential of women members and promotes their issues and interests, also had its genesis at Cecil Street in the 1980s (led by Inglis workers) before it spread throughout the whole union. The Area Council was also deeply involved in the creation of the John Fitzpatrick Housing Co-op in Richmond Hill, and its daycare facilities.

No. 25 Cecil is still controlled by the TSBA, i.e. by the union‟s workplace locals, not by the international union itself, which is a tenant. The ample parking, and its proximity to City Hall, Queen‟s Park, Ministry of Labour, law courts, arbitration centres and many downtown institutions, plus a commitment to the neighbourhood, have induced the Toronto Area Council to stay put on Cecil Street for over 60 years, despite losing thousands of manufacturing members downtown. Serendipitously, the members of the biggest USW Local in Canada, representing 7,000 University of Toronto support staff, now work conveniently nearby on the campus across College Street. Their Local 1998 has its offices in the building.

And to this day the Steel Hall perpetuates Cecil Street tradition by providing meeting space every week for countless progressive labour, community, political and social events.

Although headquartered at No. 25 Cecil for the past four decades, the Steelworkers are now also sole owners of No. 33, having bought out the clothing unions in 1995. From 1997 to 2007, this building served as Provincial H/Q for the New Democratic Party, while space in its basement and first floor lobby was occupied by USW locals, the Lifeline Foundation, and the Dental Clinic. In 2008 the whole building was refurbished and occupied by Greenpeace Canada. The original street-front area where the Old Folks Home stood [p.30] is now a paved garden (shown below). The Greenpeace renovation incorporated several progressive environmental features, notably geothermal heating & cooling, which involved drilling 450 feet below ground to tap the Earth‟s energy; energy efficient windows; lighting with motion sensors; FSC-certified wood; and reclaimed terrazzo flooring.

Another footnote: How the land behind 37-43 Cecil became the Steelworkers‟ second (west) car park

In 1884, a plot of land beside and behind No. 123 Huron St was sectioned off into designated lots [see plan below]. The land was separated on three sides by a laneway marking it off from the vacant lots on Cecil, to the north, and from built-upon lots on Baldwin, to the south. The land to the east of the plot was as yet undeveloped and unsectioned, probably because it was marshy.

In 1890, the owner of this plot was Alexander McDonnell [see plan below]. The lots to its north, on Cecil Street, had now been built upon. The formerly vacant land to its northeast on Cecil, and some vacant land to its southeast on Baldwin, had also been sectioned off and built upon. The west side of Beverley was built up too. A laneway had been extended eastward from the middle of McDonnell‟s property, dividing the Cecil and Baldwin lots, with an exit north on to Cecil Street alongside No. 23.

By 1913 [see plan below] new houses were built on McDonnell‟s land, south of 123 Huron. Behind them, some temporary outhouses and sheds had been erected on the remaining land.

In 1936, an extension was built on to the back of the Old Folks Home at No. 33-35 [see plan below]. Its south wall abutted the laneway linking the plot of land to Cecil Street, which ran west-east then exited north alongside the house at 23 Cecil.

1941 -1947 [see below]: part of the land behind No. 123 Huron was seemingly used by the Old Folks Home. It was fenced off, perhaps as a vegetable garden. Temporary buildings and sheds were also on site

In the 1950s, per John Fitzpatrick, this plot of land was owned by John Lynch, an old rag & junk collector, who stored his horse, wagon and goods in an old shed there. He accessed his property from the laneway off Huron. In the fall of 1958 his shed caught fire and burned to the ground. The horse was saved but the Ontario Federation of Labour offices on the second floor/ SW corner of 33 Cecil were damaged. The City of Toronto wouldn‟t allow Lynch to rebuild and his widow put the land up for sale. After some haggling, the TSBA bought it for $25,000, which included the north-south section of the laneway which Mrs Lynch claimed she owned rather than the City. It thus became today‟s Steelworker „west parking lot‟. To prevent illegally parked and abandoned vehicles in the unsupervised lot, a six foot chain link fence was erected, with lockable gates at the entries from Cecil and the two laneways off Huron. But drivers, eager to park there, periodically cut the chains & padlocks, so the laneway entrances from Huron were eventually welded shut.

After the Steel Hall was completed in 1972, the former back yards of Nos. 23-31 Cecil became its first (main, east) car park. Today the public laneway that runs south off Cecil gives access to both of these Steelworker car parks, as well as to the rear of houses on Beverley & Baldwin.

Next Month - The East End of Cecil St.

![Clearing the ground, pouring foundations .The Polish Hall, former Zionist Institute, is visible straight ahead centre, across Cecil street [arrowed above]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/513f806fe4b03d61808647ba/1478015041080-89QY47ORJ419A57EVVGV/image-asset.jpeg)

![Goad‟s 1924 plan, retouched to show 1936 change]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/513f806fe4b03d61808647ba/1478191266411-VBDZQN84MYNOCE7AI9UL/image-asset.jpeg)

![[Goad‟s 1924 plan, retouched to show changes made by 1947]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/513f806fe4b03d61808647ba/1478191428394-KS1JR50LR6I1KDMHWG96/image-asset.jpeg)