Part Two - The Jewish Cecil Street

The character of Cecil Street began to change dramatically from the second decade of the 20th Century. Spadina & Kensington - indeed the whole area bounded by College/Dundas and Bathurst/University - became a magnet for Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. Between 1901 and 1931, Toronto‟s population quadrupled to over 600,000, while the Jewish community multiplied fifteen-fold, to 45,000. It became the largest non-British group, at 7%, with the Italians second at 2%. As the Anglo bourgeoisie moved out (to Forest Hill, Rosedale, the Beaches), single-family occupancy of Cecil‟s spacious Victorian homes became interspersed not only with multi-family residences, but above all with institutional use. A fertile array of organizations representing the new immigrant community – social, cultural, religious, recreational, political, educational, charitable - sprang up and squeezed into the multiple spaces offered by the previous century‟s housing stock, now converted into offices and meeting rooms. Cecil - like nearby Henry, Beverley, Baldwin & D‟Arcy Streets – was soon crammed with landsmanschaften (welcome societies and loan agencies for immigrants from one particular region or town), mutual benefit associations, one-room synagogues, mini-schools, political clubs and cultural institutes, all catering for the Yiddish-speaking working class of the streets around.

The city establishment was wary of this incoming wave. Witness the mixed reaction in 1920 to the proposed opening of a synagogue inside one of the original big houses, No. 28 Cecil:

Those expressions of concern were muted and genteel compared to the vituperative anti-semitism espoused by the Toronto Telegram in its editorial of 22 September 1924:

“An influx of Jews puts a worm next the kernel of every fair city where they get hold. These people have no national tradition .. They engage in wars of no country, but flit from one to another under passports changed with chameleon swiftness, following up the wind the smell of lucre”

But whether the Telegram liked it or not, the tide was irresistible. By 1922, per the Toronto

Directory of that year, two-thirds of Cecil Street residents had Jewish-sounding names:

In 1922 the Delamere residence at No. 24 was purchased by the Labour Zionist Order, a.k.a. the Jewish National Workers Alliance, a.k.a. the Farband.

Zionism – the drive to establish a Jewish homeland in the Biblical lands of Israel - was virtually an instinctive „given‟ within Toronto‟s Jewish community, particularly after the British government‟s 1917 Balfour Declaration. It was a reflexive communal response to the anti-semitism and destruction of Jewish life in Eastern Europe. But practical expressions of Zionism covered a wide political spectrum, each with differing emphases and priorities. Labour Zionism was the main strand in the Spadina area. It was secular, socialistic, supportive of small-scale kibbutzim settlements in Palestine, but above all committed to labour union struggle in Canada. It was quite distinct from the right-wing, exceptionalist, chauvinistic and orthodox-religious forms of Zionism that are dominant today, and which defend and promote Israel as a Jewish State. Yet it is true that none of these groups - left, right or centrist – showed much, if any, awareness of, interest in, or consideration for, the political fate and socio-economic interests of Palestine‟s Arab population.

The Farband was the main expression of left Labour Zionism. It was a mutual benefit society, providing health coverage and social assistance to hundreds of new immigrant workers in the garment industry and local retail. It operated a Library and an Educational Institute, which ran the Farband Folks Shul or Bialik Shul (forerunner of the Bialik Hebrew Day School which moved up to 2760 Bathurst in the early 1960s). It supported a host of economic, labour, social, cultural and political activities, forging close ties with the unions which were springing up to represent and provide benefits to needle trades workers, furriers, hatters etc. Its politics were radical, socialist, often openly Marxist, fed by bitter experiences in Eastern Europe and by the rigours of working life in the garment factories of lower Spadina. The October 1917 Revolution in Tsarist Russia, homeland of many of these immigrants, stoked an intense rivalry between the communist-sympathizing Farband and the more centrist, social-democratic Jewish organizations and unions located further down Spadina. In later years, the Farband itself drifted to the centre, while maintaining a pro-union orientation. It conducted annual fundraising drives for the Histadrut (Jewish Labour Federation) in Palestine/Israel.

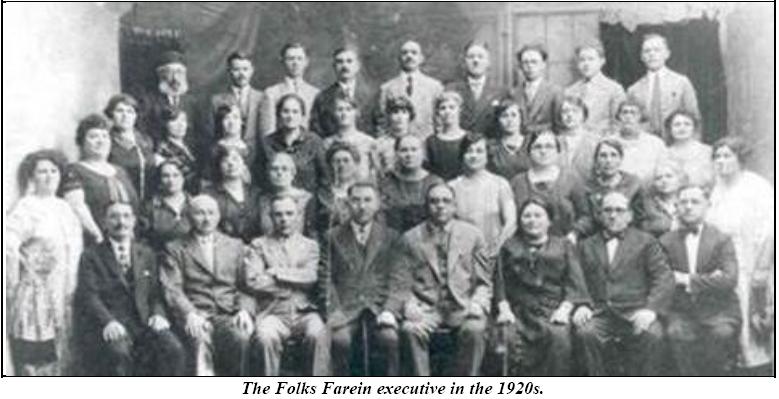

Next door to the Farband, in the other half of the building (No. 26 Cecil, purchased from the Watson family in 1921) was one of several premises on Cecil Street occupied by the Hebrew National Association, better known by its Yiddish name Folks Farein, or „People‟s Organization‟. Primarily a social welfare organization, it provided medical advice and social support to newcomers to Toronto, particularly to the bedridden and those in hospital. Its first location and headquarters from 1914 onwards, had been No. 23 Cecil across the street:

In addition to Nos. 23 & 26, the Farein also eventually occupied Nos. 27 & 37 on the south side of Cecil. It worked closely with the Jewish Old Folks Home at the adjacent Nos. 29/31 & 33/35.

A good idea of its wide range of activities can be gleaned from the following report in the Canadian Jewish Review of 26 October 1928:

Initially the Folks Farein was set up to counteract the efforts of Christian groups which, in addition to street corner soapboxes, used charitable relief and medical help to proselytize among poor Jews. Several „settlement houses‟ intended to further this cause had been set up in the Kensington Market area, notably the Presbyterians‟ St. Christopher House in 1912 - which sought to assist and „acculturize‟ newcomers - and the Anglicans‟ Nathanael Institute in 1916, predecessor of St Stephen‟s Community House, whose stated mission was to “work among the Jews”. The Scott Mission was another such group, formed in 1912 (at Elm & Elizabeth) as the Presbyterian Mission to the Hebrew People of Toronto, led by Rev. Shabetai Benjamin Rohold, renegade son of the Head Rabbi of Jerusalem. It moved to Spadina just north of College in the late 1930s, headed by Rev Morris Zeidman, a Polish-born Jew who converted to Christianity in England. The Mission acquired adjoining buildings, and quickly became a major distributor of food parcels & clothing, a soup kitchen and overnight shelter. It should be said that these missionary efforts were largely fruitless, and soon fizzled out, although distrust between the communities lingered for years.

The Farein provided childcare for working mothers, a reading room, English language classes, and hospital visitation. As the missionary threat receded, it became a purely philanthropic social welfare body, ministering to the sick and needy; providing dentures, eyeglasses, orthopaedic shoes, crutches and artificial limbs; distributing kosher meals; and helping obtain pensions for seniors, children‟s allowances for needy families, and food and billets for the unemployed.

After the second world war, in the teeth of Federal indifference, the Folks Farein sponsored over to Toronto hundreds of holocaust survivors (a.k.a. „DPs‟) from European settlement camps, and found them work in the factories of lower Spadina. But by then the Jewish character of the area was already diluted, as its population left for other parts of town.

In the 1930‟s the Farein sold No. 26 to the Farband, which, as sole owner now of both halves of the building, converted it into one single unit instead of two. Goad‟s 1941 street plan records this new No. 24 as “the Jewish School”, i.e. the Bialik. From 1953, the National Federation of Labour Youth, affiliated to the Communist Party of Canada, rented part of the premises [?details to be confirmed]. In 1959 the Farband followed other downtown Jewish organizations and moved up to Viewmount Avenue near Bathurst & Lawrence, having sold the 24 Cecil building to the Communists. Previously based above Tip Top Tailors at College & Spadina, the party had deep roots in the area. As well as housing its offices and a library, No. 24 became a venue for its public meetings & classes. In its basement, around 1964, noted artist and cartoonist Avrom Yanovsky painted a stunning mural of Dr. Norman Bethune – a medical pioneer and activist in the Spanish Civil War and then the Chinese Revolution. Both Yanovsky and Bethune were party members.

In June 1980, the building was fire-bombed during the night and burned to the ground. The perpetrators were never identified. Miraculously, the Bethune mural survived, but nothing else did. A network of eavesdropping devices was found amidst the smoking rubble.

The destroyed building was quickly rebuilt from foundations up by volunteer labour as an exact historic replica, with upgraded masonry and construction frame. It reopened in 1982.

Ten years later, in 1992, as the Soviet Union and Socialist Europe crumbled, a split within the Communist Party led to a hemorrhage of members and a bitter internecine struggle over its assets: its press, publishing house, bookshop and print shop, and above all No. 24 Cecil. One group, which had captured the leadership, sought to dissolve the party in favour of a vaguely hoped-for „broad left‟ formation, but the majority of members were determined to hold on to its Marxist-Leninist roots. Lawyers finally reached a settlement whereby the „liquidator‟ group took almost all physical assets (which they then sold) while the „party faithful‟ held on to little more than the name and the archives. The party reconstituted itself and resumed operations on the Danforth.

The property was bought by a real estate consortium, Cecil Lighthouse Ltd, which in 1993 leased it to an evangelical Christian group called The Church in Toronto. This organization - part of the Living Stream Ministry inspired by „apostles‟ Watchman Nee (1903-1972) and Witness Lee (1905-1997) - was rooted in the Chinese community that came to Canada after the Communist Revolution. Ironically, its tenure was also riven by internal divisions, both constitutional and scriptural, and by bitter legal wrangling. Its tenancy ended in 2011. Financial troubles and divisive legal disputes also plagued the owners of the property post-1992. The holding company went bankrupt in 2014, and its assets were bought by DBDC Holdings, another real estate consortium, headed by Dr. Bernstein of Dr. B. Diet fame.

In 2012 the premises were leased by Gilda‟s Club, named in memory of Second City comedienne Gilda Radner. It provides social & emotional support to individuals and families living with cancer.

The interior has been extensively renovated and upgraded, and the front doors painted iconic red.

The south side of Cecil Street

The Toronto Jewish Old Folks’ Home 1917-1954

The Ezras Noshem Society, a mutual benefit society for working-class Jewish women, provided financial support and homecare during illness or injury. It identified the need for a residential home in Toronto where poor elderly members of the Jewish community could get kosher meals and communicate with staff in Yiddish. They raised funds and in 1917 bought the semi-detached Victorian house at No. 31 Cecil, directly across from No. 24, to create the Jewish Old Folks‟ Home. It opened a year later, with a small staff. Volunteers made beds, cooked meals, did laundry and conducted fundraising. In the early 1930‟s they purchased the adjoining house, No. 29.

By 1936 the Home had also taken over the neighbouring building, No. 33/35 Cecil, and had 115 residents. That year, to keep up with increasing demand, a large new custom-built, 2-storey extension was built on to the back of No. 33/35. The Home‟s various premises now included a synagogue (at No. 35), hospital wards (at No. 29), and a space for social activities. But by the end of the War a larger, more modern, hygienic, custom-built facility for the elderly and infirm was clearly needed. A vigorous fundraising campaign was successfully waged, and in 1948 a 25-acre site was purchased in North York. By 1954 the Home had moved north to spanking new premises at what became known as the Baycrest Centre for Geriatric Care, 3650 Bathurst, which has continued to expand and prosper since.

No. 33/35 Cecil Street (above, with residents visible in the doorway) had become the main facility of the Old Folks‟ Home. When the Home moved up to Bathurst in 1954, both 29/31 and 33/35 Cecil were sold to the Toronto Area Council of the United Steelworkers of America (USWA), which represented workers at a multitude of downtown manufacturing plants, and which needed office and meeting space to service their needs.

Leftist politics on Cecil Street. An excerpt from Ben Lappin: “May Day in Toronto”

Commentary May 1955 p. 476-479

Joseph Baruch Salsberg of Cecil Street:

Elected Communist Member of Provincial Parliament 1943- 1955

J.B. Salsberg was born in 1902 to Abraham and Sarah Gitel Salsberg in the small town of Lagow, Radom, in what is now Poland. In 1913 he emigrated to Toronto, aged 11, to join his parents. They lived in the row end house at No. 73 Cecil - across a laneway and car park from the rear of a doctor‟s residence at 379 Spadina (later Grossman‟s Tavern). His devoutly religious father worked as a rag & junk peddler, doing rounds with horse & cart, to support his wife and 7 children. In the late 1920s they moved a few houses along to a slightly bigger home at No. 59 Cecil.

After two years, aged 13, Joseph dropped out of Lansdowne Public School (which is still located at Spadina Circle). He worked full-time in sweatshops for $3 a week, but studied at night to become an Orthodox rabbi. His work experiences led him to labour activism within the garment workers unions, fighting for better wages and conditions. At age 16, he told his traditionalist parents that he was abandoning Talmudic studies; he had become “a secular humanist”.

The 1922 Toronto Directory records the family thus:

Salsberg, Abraham, pdlr, h 73 Cecil

Salsberg, Jos, cap mkr, Cooper Cap Co, h 73 Cecil

He joined a Labour Zionist workers' group, the Young Poale Zion, and quickly rose in its ranks. From 1922 to 1924, he headed to New York City to serve its general secretary, edit its newspaper and conduct speaking tours across the continent. Then he returned to Toronto as an organizer for the Hat, Cap & Millinery Workers Union of North America. In 1927 he married Dora Wilensky, a social worker who eventually headed Jewish Family and Child Services.

By 1926, Salsberg's trade unionism and socialism led him to become an active member of the Communist Party of Canada. He became vice-president of the International Hatters' Union and a member of the CP Central Committee. He was well known among Jewish workers employed in the garment district of lower Spadina. His eloquence as a public speaker was famed. He was active in several unionization drives across Canada. In 1932, he became Southern Ontario organizer of the Workers Unity League, a communist-led group which sought to replace traditional US-based craft unions with industry-wide Canadian unions.

In 1938, he was elected Toronto city alderman for Ward 4, which included the largely Jewish working class neighbourhood around Spadina and Kensington Market. He became known throughout the city for his work on social issues. He tackled anti-communism with humour. Heckled by adversaries as a puppet of Joseph Stalin, Salsberg cracked back: "You're right. I got a telegram from Joe Stalin this morning ordering me to ask for a park for Ward 4."

In the 1943 provincial election he ran as a candidate in the downtown riding of St. Andrew for the Labor-Progressive Party (the legal name used by the Communist Party of Ontario after it was banned in 1941). He defeated Liberal incumbent J.J. Glass by 5,150 votes. A fellow communist A.A. MacLeod represented the adjacent riding of Bellwoods. Salsberg was re-elected in 1945, 1948 and 1951, and for several years he was the only elected communist in North America.

Salsberg was a popular MPP both inside and outside the house, respected by members of all parties. Tory Premier Leslie Frost named Salsberg Township in Northern Ontario in his honour. He was instrumental in getting the 1944 Racial Discrimination Act passed, after notices had been posted banning Jews and Blacks from various Toronto swimming pools, and other instances of anti-Semitism and racism in the province. This led to the eventual passage of the Ontario Human Rights Code.

In 1955 he lost his seat to Alan Grossman, an insurance agent, also Jewish, and father of future Ontario Premier Larry Grossman, at the end of a vicious Conservative red-baiting campaign. This was at the height of the Cold War, in an era dominated by revelations and rumours about Stalin‟s crimes. He ran unsuccessfully in the federal election later that year.

In 1957 he left the Communist Party - mainly over the issue of anti-semitism in the Soviet Union - although for some years he remained a member of the United Jewish People‟s Order, a fraternal organization of the Party. After his wife Dora died in 1959, he withdrew from public life and sold insurance for a living. He died in 1998 at the ripe old age of 95.

A Tale of Two Shules:

– one a Church, then a Synagogue, then a Chinese Catholic Centre, then a City Community Centre;

– the other a Synagogue, then a Russian Orthodox Church.

“A daughter’s afterword” (reminiscences of Cecil Street)

1. The Ostrovster Synagogue

In 1891, Protestant Toronto made a belated gesture of defiance on Spadina, with the erection of an imposing new revivalist, evangelical church at the western end of Cecil. Building this Church of the Disciples of Christ represented a major leap of faith for the „Christadelphians‟ – they suddenly upgraded themselves from renting a succession of hand-me-down mission halls to owning a custom-built, impressive, solid temple of worship

But their timing was all wrong. Jewish immigrants had begun to flood into the area. As Reuben Butchart wrote in his 1949 official church history (“The Disciples of Christ in Canada since 1830”): “We discovered in Cecil St. that we were a mere island, surrounded by a sea of European faiths and tongues. Our home missionary territory had become foreign-missionary ground.” The church withered on the vine. By 1925 it had been sold and converted into the Ostrovzter Synagogue (named for Ostrowiec, Poland). Its Disneyworld-like spire and bell tower were replaced by a dome, inside which they hung a brass chandelier. An upper gallery for women was built. A magnificent doorway was installed. Big white marble tablets, inscribed with founders‟ names in gold Hebrew lettering, were affixed in the entryway. All these features can still be seen today. In Butchart‟s words, “The Old and New Testaments were reversed on that property”

But by the 1960s, it was the Ostrovzter‟s turn to find itself stranded. Chinatown around Bay & Queen was being razed and redeveloped, pushing the Chinese west and the Jews north. The Ostrovzter congregation moved to North York, and its Cecil Street temple fell into disuse. In 1966 it became a Chinese Catholic Centre for a few years. And in 1972 it was briefly a base for the pioneer gay rights Community Homophile Association of Toronto (CHAT), led by George Hislop.

August 1972 : One of North America’s first Gay Pride Festivals. Hugh Brewster addresses a CHAT rally from the 58 Cecil fire escape.

Note the dilapidated state of the building’s entrance way

No. 58 Cecil then stood derelict for years until finally, in 1978, it was bought by the City of Toronto and converted into the Cecil Community Centre. So it remains today, used especially, but not exclusively, by local Chinese groups and individuals, with a Chinese language library upstairs.

Much of the synagogue’s internal architecture has been retained. Its acoustics are renowned for their excellence.

2. Beth Jacob Synagogue

At the other (east) end of Cecil stands the former Henry Street synagogue. Toronto‟s orthodox Beth Jacob Congregation was founded in 1899 by a group of Polish-born Jews seeking to retain traditional practices and melodies in their worship. In 1905 they purchased a small Baptist church on nearby Elm Street, but quickly outgrew it. In 1920, the City gave them permission to build a brand new synagogue on Henry Street, facing along Cecil, which was completed in 1922:

An impressive stone staircase fronted the building, leading up to the three entrance doors.

A 1930s wedding is shown below, spilling out over those steps:

But its congregation eventually drifted away from downtown and found new places to worship in uptown neighbourhoods. In 1966, the building was sold to Holy Trinity Russian Orthodox Church, with the proceeds used for a new Beth Jacob synagogue in Downsview. It still houses the Russian Church today, decked out with Eastern Rite icons and ornate crosses. It appears to be thriving – witness the Steelworkers car park on Saturdays and Sundays! – and has recently undergone extensive superstructure renovation:

One distinctive feature of the building‟s interior, under current use, is the absence of seating.

There are no pews. The congregation stands throughout the services.